Li Po and Tu Fu: Poems by Li Po

Li Po and Tu Fu: Poems by Li Po

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

WHAT EVERY EDUCATED CITIZEN OF THE WORLD NEEDS TO KNOW IN THE 21ST CENTURY: INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMORTAL TANG DYNASTY POETS OF CHINA—-LI BAI (LI PO), DU FU (TU FU), WANG WEI AND BAI JUYI—–THE MEETING OF THE BUDDHIST, TAOIST AND CONFUCIAN WORLDS—–FROM THE WORLD LITERATURE FORUM RECOMMENDED CLASSICS AND MASTERPIECES SERIES VIA GOODREADS—-ROBERT SHEPPARD, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

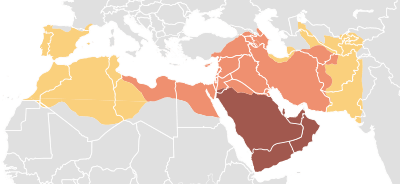

The Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) is considered the “Golden Age” of Chinese poetry and a time of cultural ascendency when China was considered the pre-eminent civilization in the world. At its commencement Chang’an (modern Xian) its capital with over one million inhabitants was the largest city on the face of the Earth and a vibrant cosmopolitan cultural center at the Eastern end of the Eurasian “Silk Road” when Europe had declined into the fragmented “Dark Ages” of the post-Roman Empire feudal era and the “Islamic Golden Age” of the Abbasid Caliphate was just beginning to rise to rival it with the construction of its new and flourishing capital at Baghdad. China itself had suffered a similar fragmentation and decline with the fall of the Han Dynasty, equal in scope and splendor to the contemporaneous Roman Empire, but with the comparative difference that Tang China had acheived reunification while Europe remained disunited and had lost much of its Classical Greek and Roman heritage, only to be recovered with the Renaissance. Tang Dynasty China by contrast was in a condition of dynamic cultural growth and innovation, having both retained its Classical heritage of Confucianism and Taoism but also assimilated the new spiritual energy of the rise of Buddhism, at the same time the European world assimilated the spiritual influence of Christianity and the Muslim world that of Islam.

Into this context were born four men of poetic genius who in the Oriental world would come to occupy a place in World Literature comparable to the great names of Dante and Shakespeare: Li Bai (Li Po), Du Fu (Tu Fu), Wang Wei and Bai Juyi. All of these geniuses were influenced by the three great cultural heritages of China: Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, just as Western writers such as Dante and Shakespeare were influenced by the three dominant Western Heritages of Greek Socratic rationalism, Roman law and social duty and Christian spirituality and moral cultivation. It was during the Tang Dynasty that Chinese culture became fully Buddhist, especially with the translations of Buddhist Scripture brough back from India by Xuanzong, the famous monk-traveller celebrated in the “Journey to the West.” Each poet was influenced by all three heritages, but with perhaps one heritage on the ascendant in each man in accordance with his temperament and worldview, with Du Fu emphasizing the social conscience and duty of Confucianism in his poetry, Li Bai the free spirit and dynamic natural balances of Taoism, and Wang Wei and Bai Juyi emphasizing the Buddhist ethos of detachment from this world and overcoming desire in quest of spiritual enlightenment.

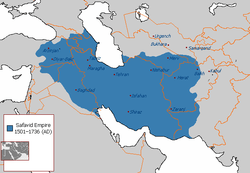

Eurasian Map Featuring the Tang Dynasty of China and the Abbasid Caliphate—Battle of Talas at Center

THE GLORIOUS TANG DYNASTY—HIGH POINT OF CHINESE CIVILIZATION

The Tang Dynasty, with its capital at Chang’an, then the most populous city in the world, is generally regarded as a high point in Chinese civilization—equal to, or surpassing that of, the earlier Han Dynasty—a Second Golden Age of cosmopolitan culture. Its territory, acquired through the military campaigns of its early rulers, rivaled that of the Han Dynasty. In censuses of the 7th and 8th centuries, the Tang records estimated the population at about 50 million people, rising by the 9th century to perhaps about 80 million people, though considerably reduced by the convulsions of the An Lu Shan Rebellion, making it the largest political entity in the world at the time, surpassing the earlier Han Dynasty’s probable 60 million and the contemporaneous Abbasid Caliphate’s probable 50 milliion and even rivaling the Roman Empire at its height, which at the time of Trajan in 117 AD was estimated at 88 million. Such massive populations, economic and cultural resources would not be matched until the rise of the nations and empires of the modern era.

With its large population and economic base, the dynasty was able to support a large proportion of its population devoted to cultural accompishments as well as a government, Civil Service administration, scholarly schools and examinations, and raise professional and conscripted armies of hundreds of thousands of troops to contend with nomadic powers in dominating Inner Asia and the lucrative trade routes along the Silk Road. Various kingdoms and states paid tribute to the Tang court, and were indirectly controlled through a protectorate system. Besides political hegemony, the Tang also exerted a powerful cultural influence over neighboring states such Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, with much of Japanese culture, government, literature and religion finding its model and origin in Tang Dynasty China.

In this global Medieval Era we can say with fairness that while Europe went into fragmentation and decline until the Renaissance the two pre-eminent centers of world civilization were Chang’an of the Tang Empire and Baghdad of the Abbasid Caliphate and the Islamic Golden Age. Two incidents characterize the interaction of these two Medieval “Superpowers,” and also affected literary production of the age: The Battle of Talas and the An Lu Shan Rebellion. The Battle of Talas of 751 AD was the collision of the two expanding superpowers, the Tang and the Abbasid Muslims, which in the defeat of the Tang Empire’s armies resulted first in the halt of its expansion along the Silk Road towards the Middle-East, and secondly, in the important transfer of Chinese paper-making technology through captured artisans from China to the Arabs, an important factor fueling the Islamic Golden Age and its literature. The An Lu Shan Rebellion, arising out of the doomed love affair of the Tang Emperor Xuanzong and the Imperial Concubine Yang Gui Fei disrupted all of China, perhaps causing the deaths of 20-30 million people, and affecting the personal lives and writings of all the poets including Li Bai, Wang Wei and Du Fu. It also was the occasion of the Abbasid Caliph sending 4000 cavalry troops to help the Tang Emperor suppress the rebellion, a force that permanently settled in China and became a catalyst for growth of the Muslim population in China and Muslim-Tang cultural interpenetration along the Silk Road. It also became the subject of the Tang poet Bai Juyi’s immortal epic of the Emperor, the Rebellion and the tragic death of the beautiful Imperial Concubine, Yang Gui Fei in “The Song of Everlasting Sorrow.”

THE COALESCING OF THE CONFUCIAN, TAOIST AND BUDDHIST WORLDS: THE PARABLE OF THE THREE VINEGAR TASTERS

The Parable of “The Three Vinegar Tasters” is a traditional subject in Chinese religious painting. and poetry. The allegorical composition depicts the three founders of China’s major religious and philosophical traditions: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. The theme in the painting has been variously interpreted as affirming the harmony and unity of the three faiths and traditions of China or as favoring Taoism relative to the others.

The three sages of the tale are dipping their fingers in a vat of vinegar and tasting it; one man reacts with a sour expression, one reacts with a bitter expression, and one reacts with a sweet expression. The three men are Confucius, Buddha, and Lao Zi, respectively. Each man’s expression represents the predominant attitude of his religion and ethos: Confucianism saw life as sour, in need of rules, ritual and restraint to correct the degeneration of the people; Buddhism saw life as bitter, dominated by pain and suffering, slavery to desire and the false illusion of Maya; and Taoism saw life as fundamentally good in its natural state. Another interpretation of the painting is that, since the three men are gathered around one vat of vinegar, the “three teachings” are one.

CONFUCIANISM

Confucianism saw life as sour, in need of rules, social discipline and restraint to correct the degeneration of people; the present was out of step with a more “golden” past and that the government had no understanding of the way of the universe—the right response was to worship the ancestors, purify and support tradition, instil ethical understanding, and strengthen social and family bonds. Confucianism, being concerned with the outside world, thus viewed the “vinegar of life” as “adulterated wine” needing social cleansing.

BUDDHISM

Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama, who first pursued then rejected philosophy and asceticism before discovering enlightenment through meditation. He concluded that we are bound to the cycles of life and death because of tanha (desire, thirst, craving). During Buddha’s first sermon he preached, “neither the extreme of indulgence nor the extremes of asceticism was acceptable as a way of life and that one should avoid extremes and seek to live in the Middle Way”. “Thus the goal of basic Buddhist practice is not the immediate achievement of a state of “Nirvana” or bliss in some heaven but the extinguishing of tanha, or desire leading to fatal illusion. When tanha is extinguished, one is released from the cycle of life—birth, suffering, death, and rebirth—only then can one achieve Nirvana.

One interpretation is that Buddhism, being concerned with the self, viewed the vinegar as a polluter of the taster’s body due to its extreme flavor. Another interpretation for the image is that Buddhism reports the facts are as they are, that vinegar is vinegar and isn’t naturally sweet on the tongue. Trying to make it sweet is ignoring what it is, pretending it is sweet—living for illusion or Maya—is denying what it is, while the equally harmful opposite is being overly disturbed by the sourness. Detachment, reason and moderation are thus required.

TAOISM

Taoism saw life as fundamentally good in its natural state.

From the Taoist point of view, sourness and bitterness come from the interfering and unappreciative mind. Life itself, when understood and utilized for what it is, is sweet, despite its occasional sourness and bitterness. In “The Vinegar Tasters” Lao Zi’s (Lao Tzu) expression is sweet because of how the religious teachings of Taoism view the world. Every natural thing is intrinsically good as long as it remains true to its nature. This perspective allows Lao Zi to experience the taste of vinegar without judging it, knowing that nature will restore its own balance transcending any extreme, via Yin and Yang and “The Dao,” the underlying Supreme Creative Dialectic driving all things and human experiences.

LI BAI (LI PO), SUPREME TANG DYNASTY LYRICIST AND TAOIST ADEPT

Li Bai (701-762) came from an obscure, possibly Turkish background and unlike other Tang poets did not attempt to take the Imperial Examination to become a scholar-official. He was infamous for his exuberant drunkenness, hard partying and “bad boy” romantic lifestyle. In his writing he chose freer forms closer to the folk songs and natural voice, though laced with playful fancy, as in the famous example of his lyric conversations with the moon. He frequented Taoist temples and echoed the Taoist embrace of the natural human emotions and feelings; that connection got him an appointment to the Imperial Court, but his misbehaviour soon ended in his dismissal. Nonetheless, he became famous and invited into the best circles to recite his works. He emphasized spontanaeity and freedom of expression in his works, yet created works of extraordinary depth of feeling:

Drinking Alone With the Moon

A pot of wine amoung the flowers.

I drink alone, no friend with me.

I raise my cup to invite the moon.

He and my shadow and I make three.

The moon does not know how to drink;

My shadow mimes my capering;

But I’ll make merry with them both—

And soon enough it will be Spring.

I sing–the moon moves to and fro.

I dance–my shadow leaps and sways.

Still sober, we exchange our joys.

Drunk–and we’ll go our separate ways.

Let’s pledge—beyond human ties—to be friends,

And meet where the Silver River ends.

Popular legend has it that Li Bai died in such a drunken fit, carousing alone on a boat on a lake, when he, drunk, leaned overboard to embrace the reflecion of the moon in the waters, and drowned.

DU FU—SUPREME POET OF SOCIAL CONSCIENCE AND ENLIGHTENED CONFUCIAN SPIRIT

Du Fu (712-770) was the grandson of a famous court poet, and took the Imperial Examination twice, but faied both times. His talent for poetry became known to the emperor, however, who arranged a special examination to allow his admittance as a court scholar-official. His outspoken social conscience, denunciation of injustice and insistence on following the pure ideals of Confucianism however, alienated higher officials and his career was confined to minor posts in remote provinces, and his travels and observations were often the occasion of his poetry. He acutely rendered human suffering, particularly of the common people, and his stylistic complexity and excellence made him the “poet’s poet” as well as the “people’s poet” for centures, as exemplified in his famous “Ballad of the Army Carts:”

Ballad of the Army Carts

Carts rattle and squeak,

Horses snort and neigh—

Bows and arrows at their waists, the conscripts march away.

Fathers, mothers, children, wives run to say good-bye.

The Xianyang Bridge in clouds of dust is hidden from the eye.

They tug at them and stamp their feet, weep, and obstruct their way.

The weeping rises to the sky.

Along the road a passer-by

Questions the conscripts. They reply:

They mobilize us constantly. Sent northwards at fifteen

To guard the River, we were forced once more to volunteer,

Though we are forty now, to man the western front this year.

The headman tied our headcloths for us when we first left here.

We came back white-haired—to be sent again to the frontier.

Those frontier posts could fill the sea with the blood of those who’ve died.

In county after county to the east, Sir, don’t you know,

In villiage after villiage only thorns and brambles grow.

Even if there’s a sturdy wife to wield the plough and hoe,

The borders of the fields have merged, you can’t tell east from west.

It’s worse still for the men from Qin, as fighters they’re the best–

And so, like chickens or like dogs they’re driven to and fro.

Though you are kind enough to ask,

Dare we complain about our task?

Take, Sir, this winter. In Guanxi

The troops have not yet been set free.

The district officers come to press

The land tax from us nonetheless.

But, Sir, how can we possibly pay?

Having a son’s a curse today.

Far better to have daughters, get them married—

A son will lie lost in the grass, unburied.

Why, Sir, on distant Qinghai shore

The bleached ungathered bones lie year on year.

New ghosts complain, and those who died before

Weep in the wet gray sky and haunt the ear.

WANG WEI–SCHOLAR-OFFICIAL, “RENAISSANCE MAN” AND BUDDHIST POET

Wang Wei was one of the most prominent poets of the Tang Dynasty, but also a famous painter, calligrapher and musician. He hailed from a distinguished scholar family, passed the highest Imperial Examination with honors and worked his way up the bureaucratic heirarchy, often assuming posts in far-away provinces. His poems displayed the high court poetic style–witty, urbane and impersonal, reinforced by the Buddhist detachment and equanimity of his religious beliefs. He became influential at the royal court until being captured in the An Lu Shan Rebellion, he was forced to work for the usurping Emperor, then punished by the reinstated Emperor. In accordance with Chan (Zen) Buddhism his work reflects the detached and melancholy view of transitory life seen as illusion. His official travels involving years of absence or threatened death far from home were often the occasion of many of of his poems:

Farewell to Yuan the Second on His Mission to Anxi

In Wei City morning rain dampens the light dust.

By the travelers’ lodge, green upon green—the willows color is new.

I urge you to drink up yet another glass of wine:

Going west from Yang Pass, there are no old friends.

BAI JUYI (BO JUYI), AUTHOR OF THE “SONG OF EVERLASTING SORROW,” TALE OF THE DOOMED LOVE OF THE EMPEROR XUANZONG AND THE BEAUTIFUL IMPERIAL CONCUBINE YANG GUI FEI

Bai Juyi (772-846) of a later generation from the other three poets, passed the Imperial Examination with honors and served in a variety of posts. He, like Du Fu, took seriously the Confucian mandate to employ poetry as vehicle for social and political protest against injustice. He also, like Bai Juyi, tried to simplify and make more natural and accessible his poetic voice, drawing closer to the people. His most immortal classic is the “Song of Everlasting Sorrow” which presents in verse the epic tragic tale of the great love affair between Emperor Xuanzong and his Imperial Concubine, Yang Gui Fei, reminiscent of the tragedy of Romeo an Juliet, which ended during the An Lu Shan Rebellion as the army accused her of distracting the Emperor from his duties and corruption and demanded her death. The poem relates how the Emperor sent a Taoist priest to find his dead lover in heaven and convey his devotion to her and her answer:

“Our souls belong together,” she said, “like this gold and this shell–

Somewhere, sometime, on earth or in heaven, we shall surely meet.”

And she sent him, by his messenger, a sentence reminding him

Of vows which had been known only to their two hearts:

“On the seventh day of the Seventh-month, in the Palace of Long Life,

We told each other secretly in the quiet midnight world

That we wished to fly in heaven, two birds with the wings of one,

And to grow together on the earth, two branches of one tree.”…

Earth endures, heaven endures; sometime both shall end,

While this unending sorrow goes on and on forever.

SPIRITUS MUNDI AND CHINESE LITERATURE

My own work, Spiritus Mundi, the contemporary epic of social idealism featuring the struggle of global idealists to establish a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly for global democracy and to head off a threatened WWIII in the Middle-East also reflects the theme of the Confucian ethic that literature should contribute to social justice and public morality. Like Du Fu it abhors the waste, suffering, social irresponsibility and stupidity of war. Like Li Bai it celebrates the life of nature and human emotions, including sexuality. About a quarter of the novel is set in China, and one of its principal themes is a renewal of spirituality across the globe.

World Literature Forum invites you to check out the great Chinese Tang Dynasty poetic masterpieces of World Literature, and also the contemporary epic novel Spiritus Mundi, by Robert Sheppard. For a fuller discussion of the concept of World Literature you are invited to look into the extended discussion in the new book Spiritus Mundi, by Robert Sheppard, one of the principal themes of which is the emergence and evolution of World Literature:

For Discussions on World Literature and n Literary Criticism in Spiritus Mundi: http://worldliteratureandliterarycrit…

Robert Sheppard

Editor-in-Chief

World Literature Forum

Author, Spiritus Mundi Novel

Author’s Blog: http://robertalexandersheppard.wordpr…

Spiritus Mundi on Goodreads:

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17…

Spiritus Mundi on Amazon, Book I: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00CIGJFGO

Spiritus Mundi, Book II: The Romance http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00CGM8BZG

Copyright Robert Sheppard 2013 All Rights Reserved